Dr Jo Grey

TMA Brisbane

Earlier this year, I accepted an invitation to spend two weeks on Guadalcanal Island, part of the Solomon Islands group supervising medical students from Bond University on an elective placement. The students were seeking a doctor to accompany them who would be happy to work alongside and supervise them in a tropical, low-resource environment. I happily accepted, having worked and travelled previously in other Pacific nations, but never visited the Solomon Islands – what a great opportunity! What a challenge!

The placement was a student initiative, organised by Bushfire, the Bond University Rural Health Club. This year is only the second year that this student-run initiative has taken place, following on from the successful inaugural trip in 2018.

As only two students were able to be funded to undertake the trip, there was a competitive selection process conducted by Bushfire. The successful candidates were from second and third year (both pre-clinical years in the Bond programme) and I met with them prior to our trip to discuss their aspirations and expectations for the elective. They were excited, filled with great ideas, a little trepidation and great anticipation for the adventure that lay ahead. We were briefed by Sam, the student organiser, who participated in the inaugural trip – expect heat, humidity, very limited medical supplies/equipment and the challenge of working with “island time”.

I arrived in Honiara a couple of days in advance of the students in order to ensure that as much as possible, administrative formalities and logistics were finalised. Small matters of ensuring I was registered as a Medical Practitioner in the Solomon Islands, contacting the Medical Superintendent of the National Referral Hospital and the Regional Health Minister and organising our transport from Honiara to Visale (a small village on the northern tip of Guadalcanal) had proved impossible to do via email, so a hands-on, on the ground approach, was required, and after much to-ing and fro-ing, all was achieved.

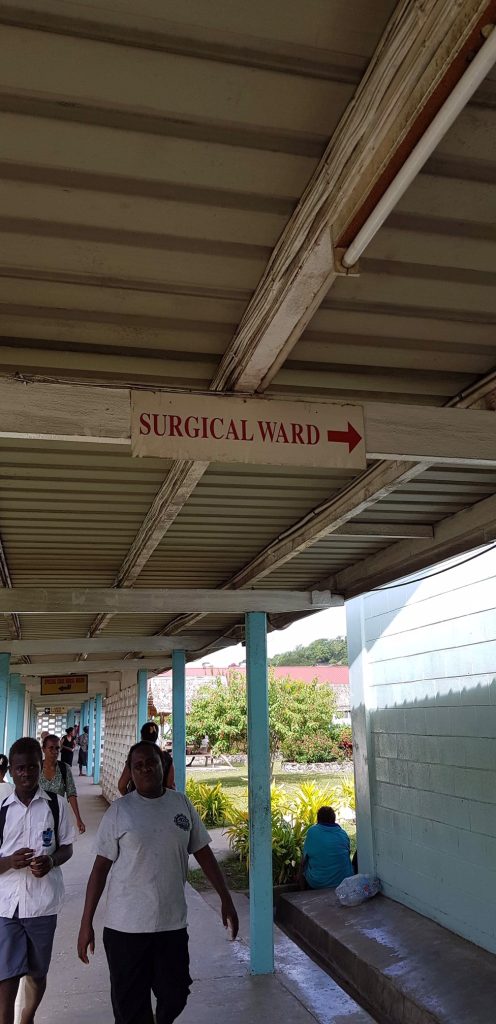

Our planned activity was to have the first week at the National Referral Hospital (NRH), Honiara, then the following week at Visale Community Health Centre. The NRH (380 beds) is the tertiary referral hospital for the Solomon Islands, although it’s facilities are extremely limited and many departments function at a suboptimal level due to lack of funding, equipment and staffing. Some sectors are well-serviced, for example, there is a Regional Eye Centre (funded through the Fred Hollows Foundation) which provides free eye care (glasses, cataract surgery and laser surgery) to Solomon Islanders. However, for renal patients, there’s no dialysis available in the Solomon Islands, so only those that are able to afford to fly to Fiji or PNG can access this treatment.

.

The students and I split our time between the two busiest hospital departments – labour ward and the emergency department (ED). Wow. There are between 300 and 400 deliveries per month at the NRH. Women are encouraged to deliver in hospital although many deliveries still take place in regional and remote clinics (as we found out in Visale). Expectant mothers present in labour, accompanied by varying numbers of family members. The labour ward is a crowded corridor like room with about 15 beds, which are rarely unoccupied, all placed end to end along the wall, leaving a narrow walking space along the ward, there’s three curtained cubicles where PV exams are performed and then a small partitioned delivery room with two delivery beds and a single radiant heat infant warmer. Quite a shock for me (having not delivered a baby for some time) and an absolute eye-opener for the students.

.

The ward is crowded, not airconditioned, clean sheets are in short supply, beds are often shared, as is the infant warmer (not uncommon to see two newborns together there). The delivery room is poorly ventilated and poorly lit (with no directional lighting to use for suturing perineal tears) and yet, it is quietly efficient, with midwives and student nurses overseeing the almost constant stream of deliveries throughout the day and night. They moved quietly from mother to mother, counting contractions, reassuring mothers, liaising with the medical staff and the families waiting outside. Babies are given BCG and Hep B vaccines at birth (literally!) as well as Vitamin K, and mothers are permitted to leave the labour ward an hour after delivery (so long as they do not have extensive bleeding and are going home with some family support). Mothers delivering overnight must wait until the following morning to be assessed and cleared by the medical staff, and to wait until the baby has been given the BCG vaccine (which is only done during day shifts). Each woman is given a take-home bundle of new plastic baby bath and nappy bucket, as well as a couple of new towels and a cotton baby wrap. We witnessed a few Emergency Caesareans (obstructed labour, breech presentation) as well as a number of stillbirths and fetal deaths in utero. Highlights were the students assisting with some deliveries, vaccinating newborns and learning to do neonatal examinations.

.

ED was a maelstrom of acute medical presentations, trauma (mainly vehicle-related or violent assaults) and a few acute on chronic medical conditions. The ED is suffering most from the drain of registered nurses from the Solomons to Vanuatu. Nurses are being lured by more generous wages in Vanuatu, with 75 resigning in September and another 60 finishing work at the NRH in December. It’s difficult to see how ED (and the wider hospital) will keep functioning if this trend continues. As one ED registrar pointed out, hospitals and clinics can run quite well with reduced medical staff, but without nurses, the whole thing grinds to a halt.

.

As part of ongoing public health surveillance, every patient who was admitted to ED had VDRL serology as a standard investigation and if found to be positive, was immediately started on a course of IM benzylpenicillin – partners were tested and commenced on treatment immediately. In the ED, the students and I were allocated our own trauma room to run on most days after early morning handover. Machete wounds, domestic violence, dog bites, multiple fractures from falling out of coconut trees (yes!) were daily cases, along with some heart-wrenching cases of advanced gynaecological malignancies. Two cases which really struck home the lack of primary health care – one 42 year old woman with metastatic cervical cancer who had been treated at her local village for back pain for the past two years, and another 68 year old woman who had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy and debulking procedure 6 months ago for endometrial cancer who presented with back pain and persistent foul-smelling vaginal discharge. For patients such as this, there is no palliative care service and once being given the news that there is no further treatment available, patients are sent home with their family to be cared for in the village until their death. For the students, this lack of services was quite confronting and we had many long debriefing sessions after our days in ED.

.

Our second week was spent at Visale, only 40 km north-west of Honiara, but a world away from the smoky, filthy streets of Honiara. We stayed with the Sisters of the Sacred Heart Parish in Visale who welcomed us with open arms and made our stay there absolutely memorable. We stayed in the postulate house, quite palatial compared to the local villages one- or two-room houses, but still without running water or electricity. So carting buckets of water every day for cooking and washing, cooking on a gas burner and using the occasional solar-powered lamp all added to the broader experience.

.

The Visale Community Clinic is run by three registered nurses who live on-site and work, two at a time, around the clock, seven days a week. They too, greeted us with open arms – their first request was for me to assess a pregnant woman with pre-eclampsia and refer her to the NRH. That done, two of the three transported the patient into Honiara and left the students and I to run the clinic for the day. We saw 75 patients that day – 75% of whom presented with fever wanting to be tested for malaria. Malaria is a huge problem in the Solomons and around 50% of those tested had P falciparum or a mixed infection of P falciparum/vivax. The clinic has Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits available (for which the nurses charge $5SBD equivalent to about $0.90AUD) and there is a microscopist on duty Monday to Friday. I was amazed that, in a country where almost nothing happens in a hurry, many patients prefer to pay for an RDT (instant result) rather than wait 20 minutes for their microscopy result (which is free). Patients who presented for malaria testing with history of fever, headaches and body aches were visibly disappointed with a negative malarial result – mainly because this meant that they were only offered paracetamol for symptomatic relief, rather than malaria treatment. Treatment was 3 days of Co-artem (artemether-lumefantrine), with a stat dose of primaquine (for P falciparum to reduce transmissibility) or 14 days of primaquine following completion of the co-artem (for mixed or P vivax infections).

.

Other common presentations were otitis media, cellulitis, lower leg ulcers and minor trauma such as lacerations. Antibiotics such as amoxicillin and cephalexin were completely out of stock (and had been for some time), so Septrin was the drug of choice for soft tissue and respiratory infections, with metronidazole widely used for oral infections (which were frequent – dental hygiene is poor and about 50% of the population over the age of 12 either smokes or chews betel nut). There were no dressings available at the clinic to dress ulcers or other wounds. I had taken a supply from home, which was soon exhausted treating the three nuns for the time that we stayed in the village (happily their wounds were well on the way to healing by the time we left). The nurses at the clinic were also kept busy delivering babies (mostly which seem to arrive at night) and managing antenatal emergencies (which I was asked to see and refer on during my stay).

.

We finished our time in Visale, totally exhausted, overwhelmed by the work the staff at the NRH and clinic do with such limited resources and grateful to our hosts for giving us the opportunity to learn in their environment. In return, we hope that sharing our experience, the donation of medical supplies we were able to leave with them and the assistance we provided during our short stay made a contribution to the clinic staff and patients.